During the long, rainy winter of 2016, I had the opportunity to entertain and educate myself about Alaska history. Here are a few surprising facts which caught my attention.

The last battle of the Civil War took place in Arctic Alaska. In 1865, eight Yankee whaling ships were burned by the Confederate steamer Shenandoah, in the waters of the Bering Strait. The battle took place two and a half months after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox; Confederate Captain James Waddell most certainly knew that the war was already over, but chose to destroy the valuable whale ships and their cargo anyway. After the news of his actions spread, he was vilified as a pirate, and fled to England — sailing directly from the Arctic to Great Britain, a non-stop 17,000 mile journey. After some legal wrangling in England, he was eventually allowed to go free, and never was tried for piracy.

The first summit of Mt. McKinley was faked. In 1906, Dr. Frederick Cook claimed to have reached the top of the 20,320-foot Denali. But there was something fishy about his story, although it took more than fifty years to debunk Cook’s claims. Mountaineer and photographer Bradford Washburn proved that Cook never reached the summit, by climbing Denali several times himself and taking photos that could be compared side-by-side with Cook’s fakes.

The Western Union Telegraph Expedition planned to connect San Francisco and Moscow by telegraph via the Bering Strait, thereby linking the North American telegraph system with Europe and Asia. Scouting missions through British Columbia, Alaska, and Siberia were conducted in 1865-67, and contributed much to the understanding of geography, geology, and botany of the region — as well as serving as reconnaissance for the impending gold rush. William H. Dall, Robert Kennicott, and Frederick Whymper were members of the expedition. The project was abandoned when the Atlantic cable was completed in 1866, although it took a year for this news to reach the expedition itself.

In June 1942, World War II came to Alaska. After forty-two residents of the island of Attu were captured and imprisoned in Japan, the U.S. government evacuated 881 Native Alaskan people of the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands. They were put into internment camps in Southeast Alaska, and were kept there from 1942 to 1945. The U.S. government did not make financial reparations to the islanders until 1988.

“Mark Pettikoff, fifty-one-year-old leader of Akutan’s Aleuts, with his wife Sophie, forty-four, and daughter Irene, two, in the entrance of their tent at Wrangell Institute. (National Archives, Still Picture Branch)” From When the Wind was a River by Dean Kohlhoff.

Captain Michael A. Healy, as skipper of the U.S. Revenue Cutters Corwin and Bear, patrolled the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean in the 1870s and 1880s. The Revenue Cutter Service was the predecessor of the U.S. Life Saving Service and U.S. Coast Guard. In Alaska, the Corwin and Bear performed rescue missions, captured poachers, transported scientists and explorers, and imported reindeer. Healy was the son of an Irish plantation owner in Georgia; his mother was a slave. Nicknamed “Hell Roaring Mike” for his vociferous leadership style, he was the first man of African-American descent to command a ship of the United States government.

In 1935, the U.S. government made a concerted effort to colonize Alaska, bringing 202 depression-era farming families from the northern Great Lakes states to the Matanuska Valley. The Matanuska Colony, located about 40 miles northeast of Anchorage, was a “generally successful experiment to increase permanent settlement in the Territory” with about a third of the original settlers still living in the colony in 1948.

Illustration from Alaska Group Settlement: The Matanuska Valley Colony by Kirk H. Stone.

Mummies have been found in the Aleutian Islands. Native people placed their dead in caves, first tenderly dressing them in their best bird skin parkas, and then wrapping them in fine woven grass mats, seal skins, dry grass, sea otter skins, and sea lion skins.

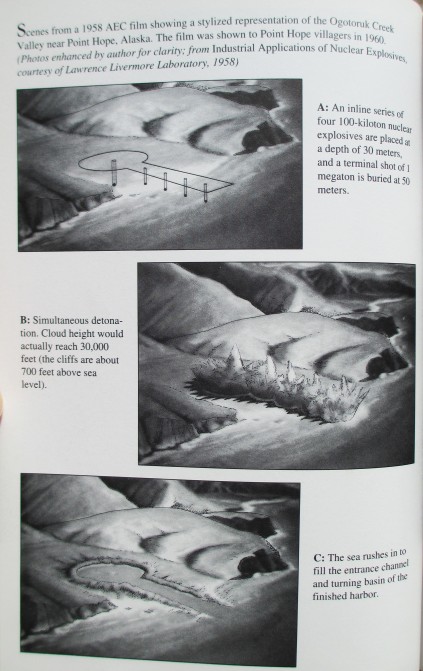

In 1958, “Father of the H-Bomb” Edward Teller unveiled a plan called Project Chariot: the creation of a harbor near Point Hope, Alaska (on the Chukchi Sea) by detonating 2.4 megatons of nuclear explosives. The project was meant to demonstrate the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Local Iñupiaq people, particularly Daniel Lisbourne, fought the project, and it was discontinued in 1962. Edward Teller said, “I was looking, contrary to regulations, straight at the bomb. I put on welding glasses, suntan lotion, and gloves. I looked the beast in the eye, and I was impressed.”

Edward Teller’s plan to use nuclear weapons for “peaceful” means. Illustration from The Firecracker Boys by Dan O’Neill.

Will Rogers traveled to Alaska in 1935, looking for the opportunity to meet some old-timers from the 1896 Klondike gold rush. He thought all the prospectors who had returned to the Lower 48 “were such liars, I would like to go up and meet the old boys that had the nerve to stick.” He and his pilot friend Wiley Post had a great time visiting Juneau, Mount McKinley, the Matanuska Colony, and Fairbanks. On the way to Barrow to meet the “King of the Arctic,” Charles Brower, their plane crashed and both perished.

Steller’s Sea Cow, the northern manatee, was described by German naturalist Georg Steller in 1742. He had plenty of time to observe the eight-thousand pound animals while he was shipwrecked on Bering Island, located between the end of the Aleutian island chain and the Kamchatka Peninsula of Siberia. “In the spring they mate like human beings, particularly towards evening when the sea is calm.” Using its front feet, “when, lying on its back getting ready for the Venus game, one embraces the other with these as if with arms.”

Steller’s Sea Cow. Illustration from Where the Sea Breaks Its Back by Corey Ford.

REFERENCES

Bockstoce, John R. (1986). Whales Ice and Men: A History of Whaling in the Western Arctic. University of Washington Press, Seattle and London.

Ford, Corey (1966). Where the Sea Breaks Its Back: The Epic Story of a Pioneer Naturalist and the Discovery of Alaska. Little, Brown and Company, Boston and Toronto.

Dall, W.H. (1878). On the Remains of Later Pre-Historic Man Obtained from Caves in the Catherina Archipelago, Alaska Territory, and Especially from the Caves of the Aleutian Islands. The Smithsonian Institution, Washington City.

Hunt, William R. (1975). Arctic Passage: The Turbulent History of the Land and People of the Bering Sea 1697-1975. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York.

Ketchum, Richard M. (1973). Will Rogers: The Man and His Times. Simon and Schuster, New York, NY.

Kohlhoff, Dean (1995). When the Wind Was a River: Aleut Evacuation in World War II. University of Washington Press, Seattle and London.

Noble, Dennis L. & Strobridge, Truman R. (2009). Captain “Hell Roaring” Mike Healy: From American Slave to Arctic Hero. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

O’Neill, Dan (1994). The Firecracker Boys. St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY.

Stone, Kirk H. (1950). Alaskan Group Settlement: The Matanuska Valley Colony. United States Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Washington.

Washburn, Bradford & Cherici, Peter (2001). The Dishonorable Dr. Cook: Debunking the Notorious Mount McKinley Hoax. The Mountaineers Books, Seattle, WA.